5 Whys

Getting to the Root of a Problem Quickly

Have you ever had a problem that refused to go away? No matter what you did, sooner or later it would return, perhaps in another form.

Stubborn or recurrent problems are often symptoms of deeper issues. "Quick fixes" may seem convenient, but they often solve only the surface issues and waste resources that could otherwise be used to tackle the real cause.

In this article and in the video, below, we look at the 5 Whys technique (sometimes known as 5Y). This is a simple but powerful tool for cutting quickly through the outward symptoms of a problem to reveal its underlying causes, so that you can deal with it once and for all.

Click here to view a transcript of this video.

Origins of the 5 Whys Technique

Sakichi Toyoda, the Japanese industrialist, inventor, and founder of Toyota Industries, developed the 5 Whys technique in the 1930s. It became popular in the 1970s, and Toyota still uses it to solve problems today.

Toyota has a "go and see" philosophy. This means that its decision making is based on an in-depth understanding of what's actually happening on the shop floor, rather than on what someone in a boardroom thinks might be happening.

The 5 Whys technique is true to this tradition, and it is most effective when the answers come from people who have hands-on experience of the process or problem in question.

The method is remarkably simple: when a problem occurs, you drill down to its root cause by asking "Why?" five times. Then, when a counter-measure becomes apparent, you follow it through to prevent the issue from recurring.

Note:

The 5 Whys uses "counter-measures," rather than "solutions." A counter-measure is an action or set of actions that seeks to prevent the problem from arising again, while a solution may just seek to deal with the symptom. As such, counter-measures are more robust, and will more likely prevent the problem from recurring.

When to Use a 5 Whys Analysis

You can use 5 Whys for troubleshooting, quality improvement, and problem solving, but it is most effective when used to resolve simple or moderately difficult problems.

It may not be suitable if you need to tackle a complex or critical problem. This is because 5 Whys can lead you to pursue a single track, or a limited number of tracks, of inquiry when, in fact, there could be multiple causes. In cases like these, a wider-ranging method such as Cause and Effect Analysis or Failure Mode and Effects Analysis may be more effective.

This simple technique, however, can often direct you quickly to the root cause of a problem. So, whenever a system or process isn't working properly, give it a try before you embark on a more in-depth approach – and certainly before you attempt to develop a solution.

The tool's simplicity gives it great flexibility, too, and 5 Whys combines well with other methods and techniques, such as Root Cause Analysis. It is often associated with Lean Manufacturing, where it is used to identify and eliminate wasteful practices. It is also used in the analysis phase of the Six Sigma quality improvement methodology.

How to Use the 5 Whys

The model follows a very simple seven-step process:

1. Assemble a Team

Gather together people who are familiar with the specifics of the problem, and with the process that you're trying to fix. Include someone to act as a facilitator, who can keep the team focused on identifying effective counter-measures.

2. Define the Problem

If you can, observe the problem in action. Discuss it with your team and write a brief, clear problem statement that you all agree on. For example, "Team A isn't meeting its response time targets" or "Software release B resulted in too many rollback failures."

Then, write your statement on a whiteboard or sticky note, leaving enough space around it to add your answers to the repeated question, "Why?"

3. Ask the First "Why?"

Ask your team why the problem is occurring. (For example, "Why isn't Team A meeting its response time targets?")

Asking "Why?" sounds simple, but answering it requires serious thought. Search for answers that are grounded in fact: they must be accounts of things that have actually happened, not guesses at what might have happened.

This prevents 5 Whys from becoming just a process of deductive reasoning, which can generate a large number of possible causes and, sometimes, create more confusion as you chase down hypothetical problems.

Your team members may come up with one obvious reason why, or several plausible ones. Record their answers as succinct phrases, rather than as single words or lengthy statements, and write them below (or beside) your problem statement. For example, saying "volume of calls is too high" is better than a vague "overloaded."

4. Ask "Why?" Four More Times

For each of the answers that you generated in Step 3, ask four further "whys" in succession. Each time, frame the question in response to the answer you've just recorded.

Tip:

Try to move quickly from one question to the next, so that you have the full picture before you jump to any conclusions.

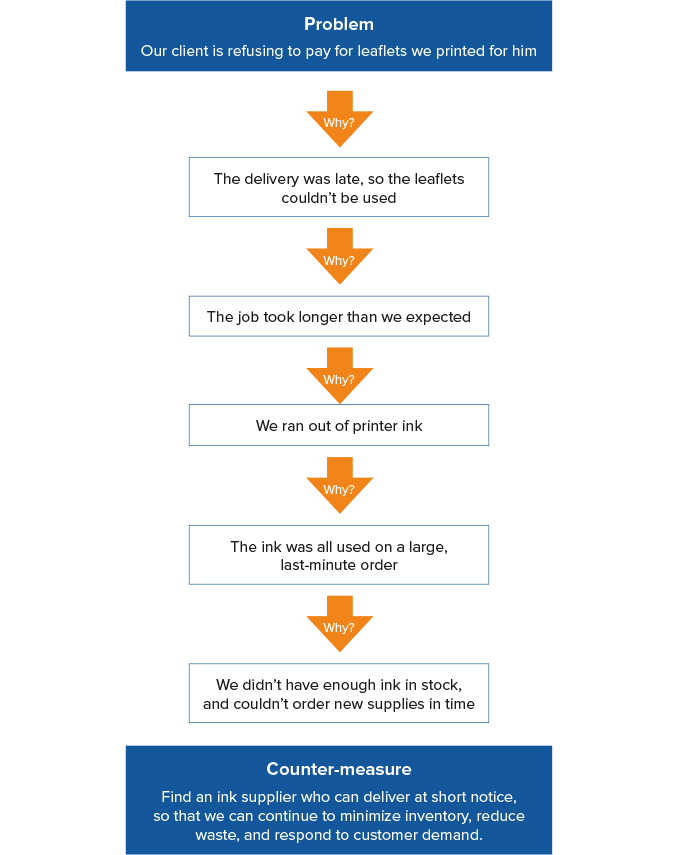

The diagram, below, shows an example of 5 Whys in action, following a single lane of inquiry.

Figure 1: 5 Whys Example (Single Lane)

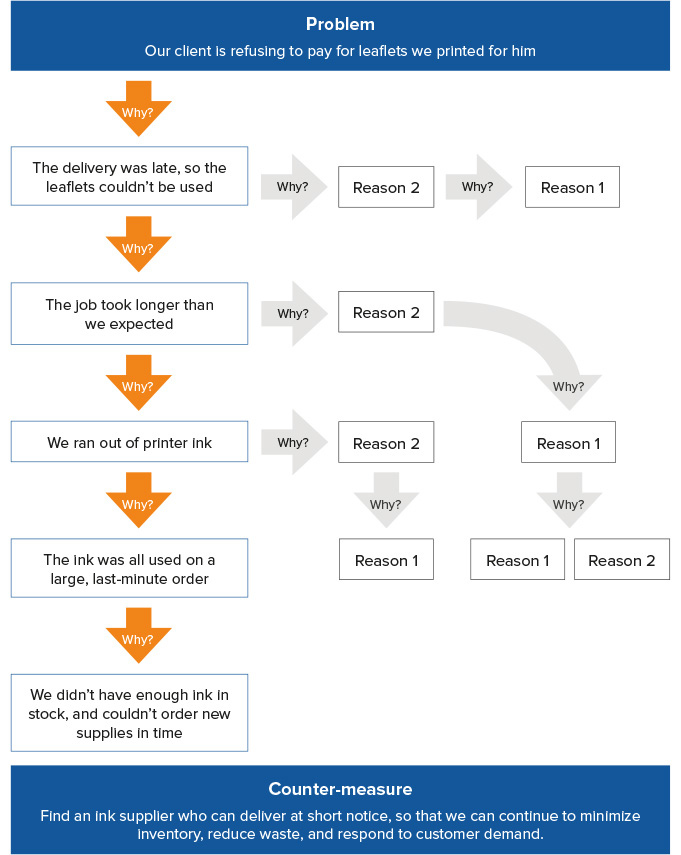

The 5 Whys method also allows you to follow multiple lanes of inquiry. An example of this is shown in Figure 2, below.

In our example, asking "Why was the delivery late?" produces a second answer (Reason 2). Asking "Why?" for that answer reveals a single reason (Reason 1), which you can address with a counter-measure.

Similarly, asking "Why did the job take longer than expected?" has a second answer (Reason 2), and asking "Why?" at this point reveals a single reason (Reason 1). Another "Why?" here identifies two possibilities (Reasons 1 and 2) before a possible counter-measure becomes evident.

There is also a second reason for "Why we ran out of printer ink" (Reason 2), and a single answer for the next "Why?" (Reason 1), which can then be addressed with a counter-measure.

Figure 2: 5 Whys Example (Multiple Lanes)

Step 5. Know When to Stop

You'll know that you've revealed the root cause of the problem when asking "why" produces no more useful responses, and you can go no further. An appropriate counter-measure or process change should then become evident. (As we said earlier, if you're not sure that you've uncovered the real root cause, consider using a more in-depth problem-solving technique like Cause and Effect Analysis, Root Cause Analysis, or FMEA.)

If you identified more than one reason in Step 3, repeat this process for each of the different branches of your analysis until you reach a root cause for each one.

Tip 1:

The "5" in 5 Whys is really just a "rule of thumb." In some cases, you may need to ask "Why?" a few more times before you get to the root of the problem.

In other cases, you may reach this point before you ask your fifth "Why?" If you do, make sure that you haven't stopped too soon, and that you're not simply accepting "knee-jerk" responses.

The important point is to stop asking "Why?" when you stop producing useful responses.

Tip 2:

As you work through your chain of questions, you may find that someone has failed to take a necessary action. The great thing about 5 Whys is that it prompts you to go further than just assigning blame, and to ask why that happened. This often points to organizational issues or areas where processes need to be improved.

6. Address the Root Cause(s)

Now that you've identified at least one root cause, you need to discuss and agree on the counter-measures that will prevent the problem from recurring.

7. Monitor Your Measures

Keep a close watch on how effectively your counter-measures eliminate or minimize the initial problem. You may need to amend them, or replace them entirely. If this happens, it's a good idea to repeat the 5 Whys process to ensure that you've identified the correct root cause.

Appreciation

A similar question-based approach known as "appreciation" can help you to uncover factors in a situation that you might otherwise miss.

It was originally developed by the military to assist commanders in gaining a comprehensive understanding of any fact, problem or situation. But you can also apply it in the workplace.

Starting with a fact, you first ask the question, "So what?" – in other words, what are the implications of that fact? Why is this fact important?

You then continue asking that question until you've drawn all possible conclusions from it.

The major difference between this and the 5 Whys technique is that appreciation is often used to get the most information out of a simple fact or statement, while 5 Whys is designed to drill down to the root of a problem.

Note:

Bear in mind that appreciation can restrict you to one line of thinking. For instance, once you've answered your first "So what?" question, you might follow a single line of inquiry to its conclusion. To avoid this, repeat the appreciation process several times over to make sure that you've covered all bases.

Key Points

The 5 Whys strategy is a simple, effective tool for uncovering the root of a problem. You can use it in troubleshooting, problem-solving, and quality-improvement initiatives.

Start with a problem and ask why it is occurring. Make sure that your answer is grounded in fact, and then ask the question again. Continue the process until you reach the root cause of the problem, and you can identify a counter-measure that will prevent it from recurring.

Bear in mind that this questioning process is best suited to simple or moderately difficult problems. Complex problems may benefit from a more detailed approach, although using 5 Whys will still give you useful insights.

Infographic

You can see our infographic on the 5 Whys method here:

This site teaches you the skills you need for a happy and successful career; and this is just one of many tools and resources that you'll find here at Mind Tools. Subscribe to our free newsletter, or join the Mind Tools Club and really supercharge your career!

Thanks for your observant feedback.

Sakichi Toyoda died in October of 1930, and is the creator of the 5 Whys. Also, he is stated as the founder of Toyota as he challenged his son to start a business that applied the principles of Lean and the 5 Whys. His son Kiichiro first continued with the loom company, and then decided he could do the same for any company, primarily a car company that he called Toyota.

BillT

Mind Tools Team

Great article. However Sakichi Toyoda died in the year 1930, so i don't see how he could have developed this technique in the 1930s. Either 1930 in his last year of life, or the date is wrong.

Also, he wasn't the founder of Toyota. His son was. However, he was the founder of Toyoda companies, but not Toyota

Welcome to the Club! Indeed this 5 Whys approach is a great technique to get to the bottom of things!

It would be great to meet you so come on over to the Forums and introduce yourself. Also if you have any questions, just let us know and we will be happy to help.

Midgie

Mind Tools Team