What Are Supply and Demand Curves?

Understanding How Quantity Effects Market Price

© GettyImages

AleksanderNakic

The laws of supply and demand determine what products you can buy, and at what price.

Imagine the scenario: you arrive at the market to stock up on fruit, but it's been a bad year for apples, and supplies are low. The price has gone up, even since last week – but you accept the increase and snap them up anyway.

On the plus side, there's been a bumper crop of pears. The growers are keen to sell as many as they can before their produce starts to rot, and they've slashed their prices accordingly. But you're in no hurry – you know that if you come back at the end of the day they'll be even cheaper.

For most of us, as consumers, these basic laws of supply and demand are so familiar, they're almost second nature: plentiful goods are cheap; scarce goods cost more. But in business, these concepts are used in a more nuanced way to examine how much of a product consumers might buy at different prices, and the quantity you should offer to the market to maximize your revenue.

In this article, we'll explore the relationship between supply and demand, and how you can use this knowledge to make better pricing and supply decisions.

The Law of Demand

Demand refers to how much of a product consumers are willing to purchase, at different price points, during a certain time period.

We all have limited resources, and we have to decide what we're willing and able to buy. As an example, let's look at a simple model of the demand for gasoline.

Note:

The gasoline prices example, used throughout this article, is for illustration only. It is not a description of the real gasoline market.

If the price of gas is $2.00 per liter, people may be willing and able to purchase 50 liters per week, on average. If the price drops to $1.75 per liter, they may buy 60 liters per week. At $1.50 per liter, they may buy 75 liters.

You can express this information in a table, or “schedule,” like this:

| Buyer Demand per Consumer | |

|---|---|

| Price per liter | Quantity (liters) demanded per week |

| $2.00 | 50 |

| $1.75 | 60 |

| $1.50 | 75 |

| $1.25 | 95 |

| $1.00 | 120 |

As the price of gas falls, the demand increases – people may choose to make more nonessential journeys in their leisure time, for example, or just top up their tanks if they anticipate an imminent price increase. But price is an obstacle to purchasing, so if the price rises again, less will be demanded.

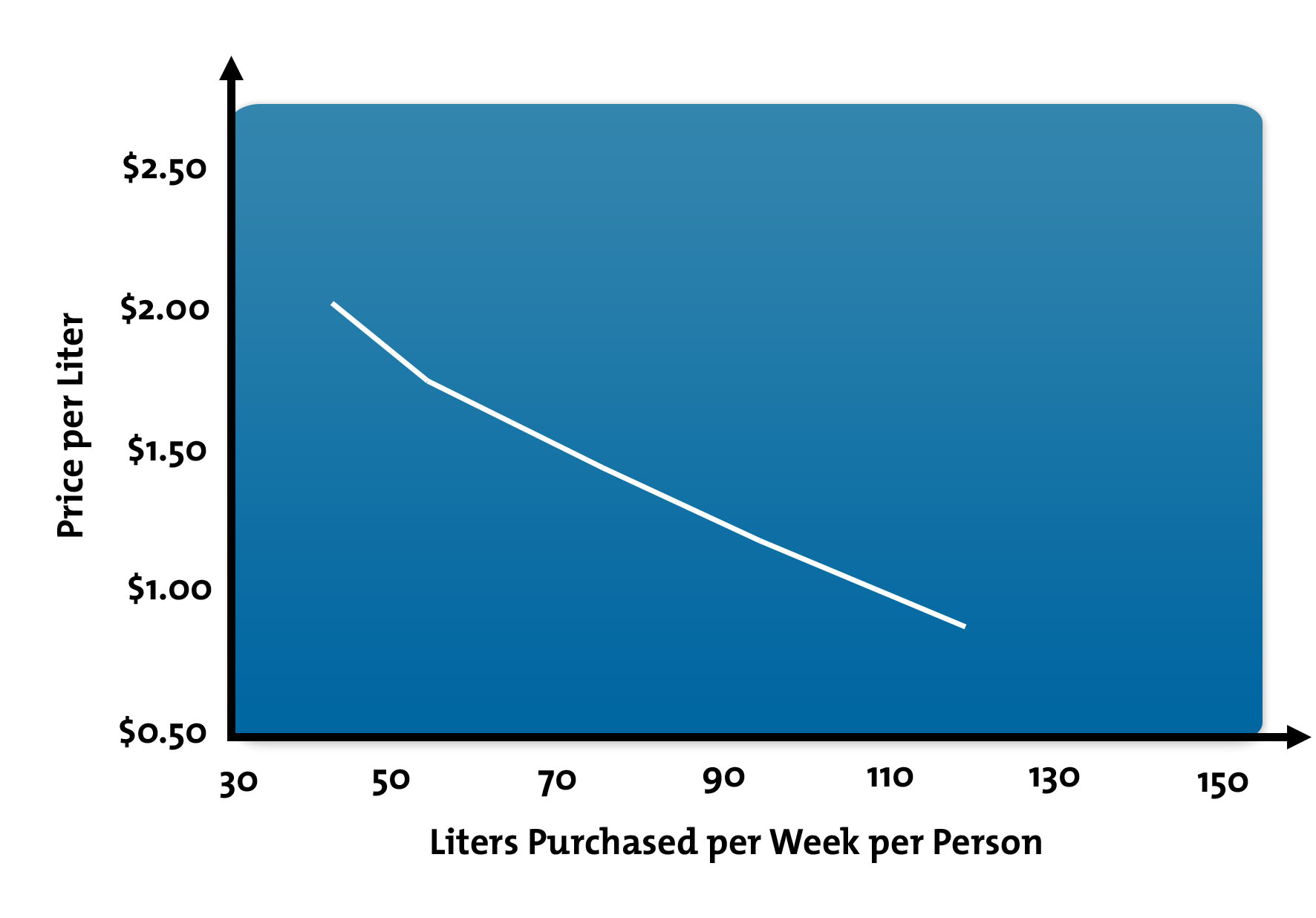

In other words, there is an "inverse" relationship between price and quantity demanded. This means that when you plot the schedule above on a graph, you get a downward-sloping demand curve, as shown in Figure 1:

Figure 1: Demand Curve for Gasoline

The Law of Supply

While demand explains the consumer side of purchasing decisions, supply relates to the seller's desire to make a profit. A supply schedule shows the amount of product that a supplier is willing and able to offer to the market, at specific price points, during a certain time period.

Note:

Supply variations occur because production costs tend to vary by supplier. When the price is low, only producers with low costs can make a profit, so only they produce. When the price is high, even producers with high costs can make a profit, so everyone produces.

In our example, the schedule below shows that gas suppliers are willing to provide 50 liters per consumer per week at the low price of $1.20 per liter. But, if consumers will pay $2.15 per liter, suppliers will provide 120 liters per week. (Remember, we've assumed a simple economy in which gas companies sell directly to consumers.)

| Gas Supply per Consumer | |

|---|---|

| Price per liter | Quantity (liters) supplied per week |

| $1.20 | 50 |

| $1.30 | 60 |

| $1.50 | 75 |

| $1.75 | 95 |

| $2.15 | 120 |

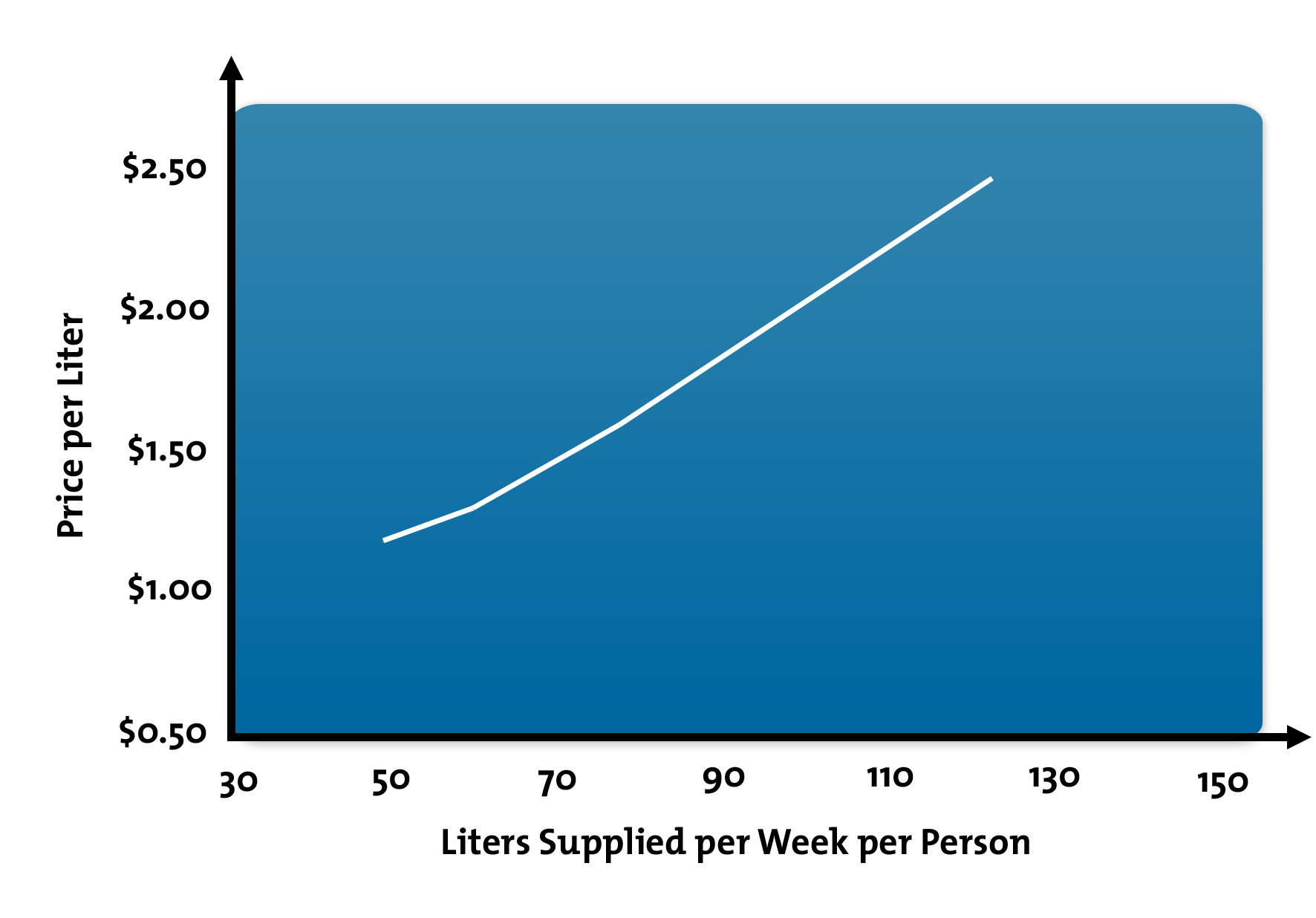

As the price rises, the quantity supplied rises, too. As the price falls, so does supply. This is a "direct" relationship, and the supply curve has an upward slope, as shown in Figure 2.

Figure 2: Supply Curve for Gasoline

Using Supply and Demand to Set Price and Quantity

So, if suppliers want to sell at high prices, and consumers want to buy at low prices, how do you set the price you charge for your product or service? And how do you know how much of it to make available?

Let's go back to our gas example. If oil companies try to sell their gas at $2.15 per liter, would it sell well? Probably not. If they lower the price to $1.20 per liter, they'll sell more as consumers will be happy. But will they make enough profit? And will there be enough supply to meet the higher demand by consumers? No, and no again.

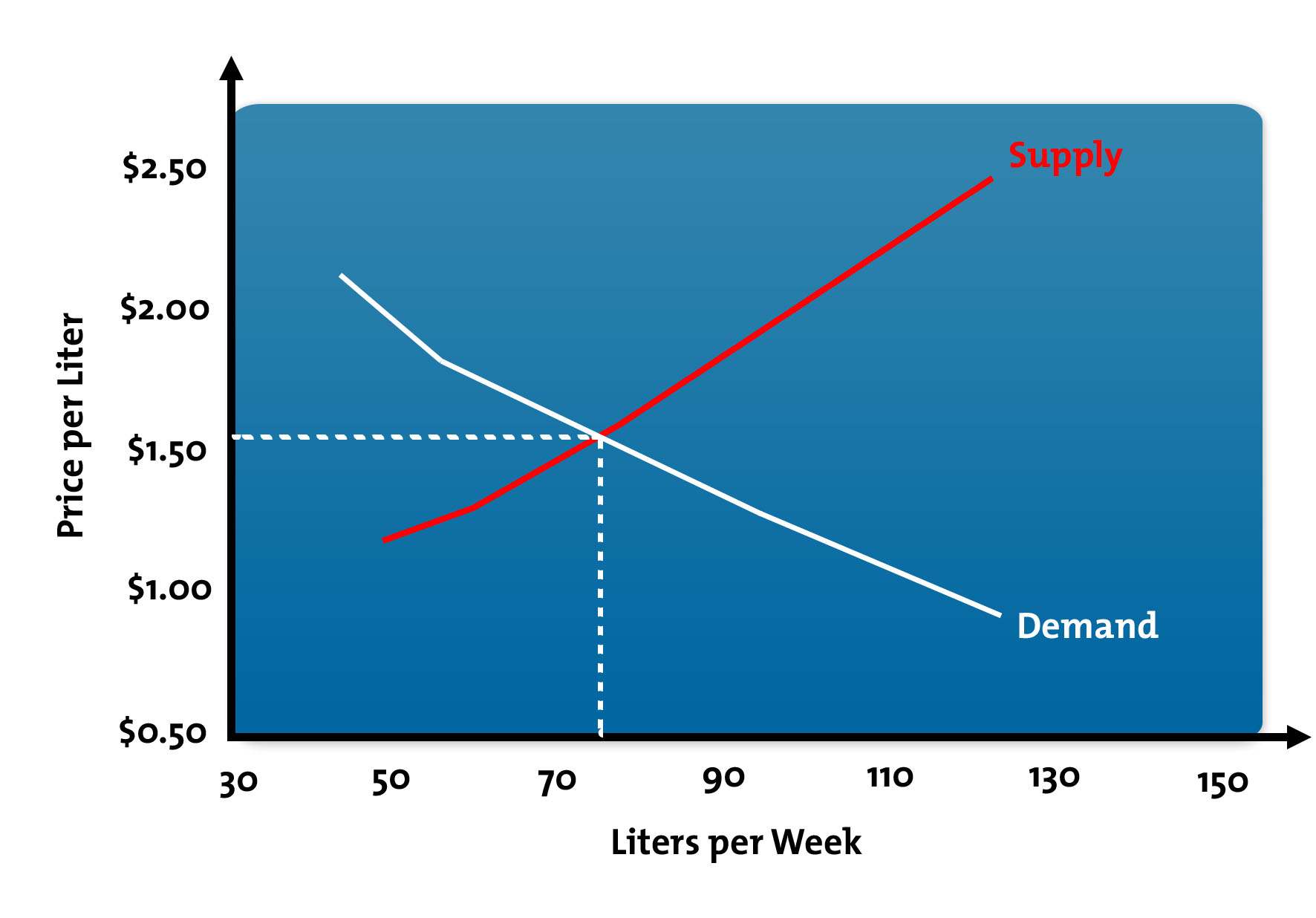

To determine the price and quantity of goods in the market, we need to find the price point where consumer demand equals the amount that suppliers are willing to supply. This is called the market "equilibrium." The central idea of a free market is that prices and quantities tend to move naturally toward equilibrium, and this keeps the market stable.

Market Equilibrium: Where Supply Meets Demand

Equilibrium is the point where demand for a product equals the quantity supplied. This means that there's no surplus and no shortage of goods.

A shortage occurs when demand exceeds supply – in other words, when the price is too low. However, shortages tend to drive up the price, because consumers compete to purchase the product. As a result, businesses may hold back supply to stimulate demand. This enables them to raise the price.

A surplus occurs when the price is too high, and demand decreases, even though the supply is available. Consumers may start to use less of the product, or purchase substitute products that are more affordable. To eliminate the surplus, suppliers reduce their prices and consumers start buying again.

In our gas example, the market equilibrium price is $1.50, with a supply of 75 liters per consumer per week. This is represented by the point at which the supply and demand curves intersect, as shown in Figure 3.

Figure 3: Market Equilibrium

Price Elasticity

When you consider what price to set for your product or service, it's important to remember that not all products behave in the same way. The extent to which the demand for your product is affected by the price you set is known as "price elasticity of demand."

Inelastic products tend to be those that people always want to buy, but generally only in a fixed quantity. Electricity is an example of an inelastic product: if power companies lower the price of electricity, consumers probably won't use a lot more power in their homes, because they don't need more than they already use. But, if electricity prices rise, demand is unlikely to fall significantly, because people still need power.

However, demand for inessential or luxury goods, such as restaurant meals, is highly elastic – consumers quickly choose to stop going to restaurants if prices go up.

So, if demand for the products or services that your company offers is elastic, you may want to consider methods other than raising prices to increase your revenue – such as economies of scale or improving production efficiency, for example.

Changes in Demand and Supply

As we've seen, a change in price usually leads to a change in the quantity demanded or supplied. But what happens when there's a long-term change in price?

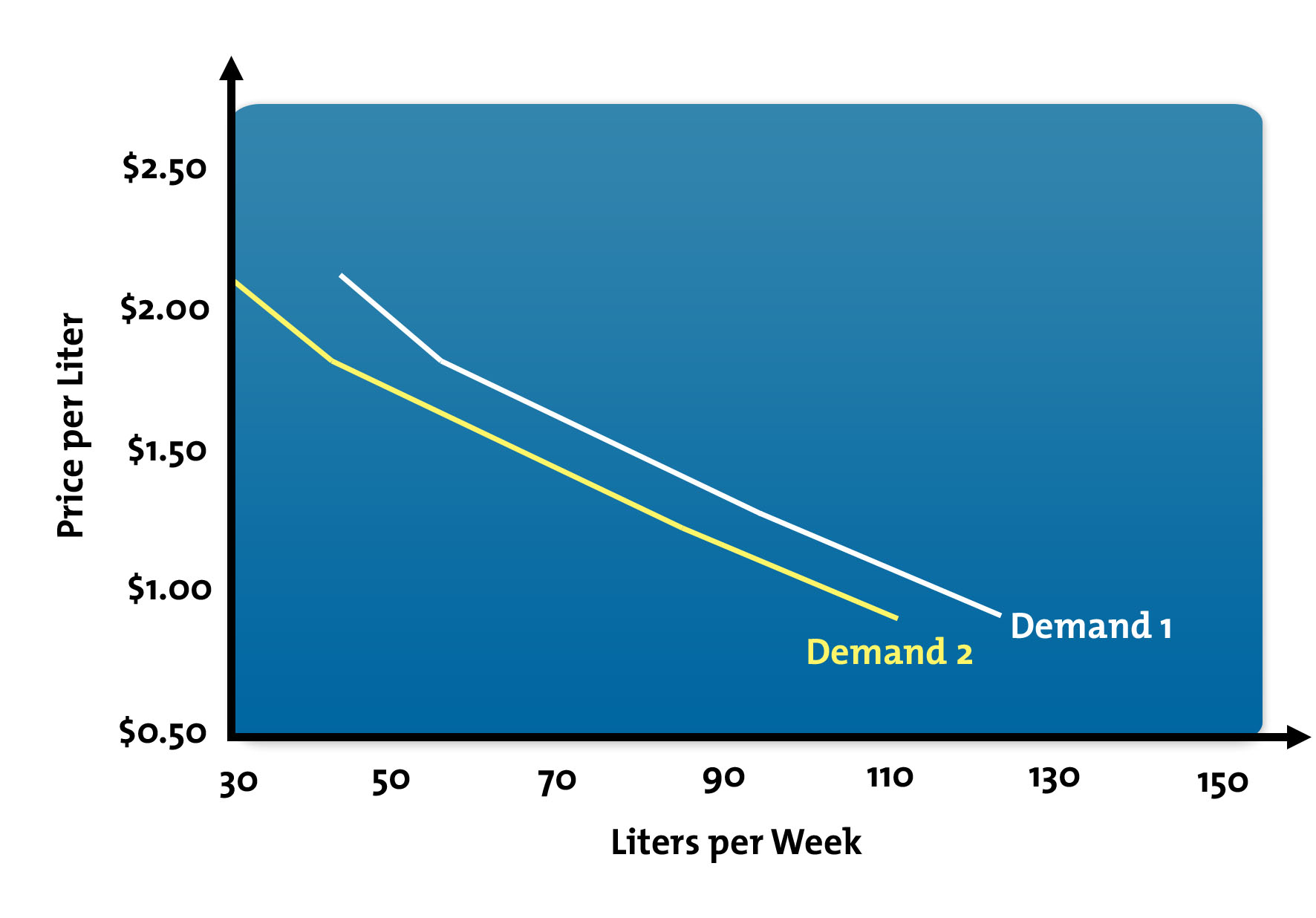

Let's return to our gas example. If there's a long-term increase in the price of gas, the pattern of demand changes. People may start walking or cycling to work, or buy more gas-efficient vehicles. The result is a major change in total demand and a major shift in the demand curve. And, with a shift in demand, the equilibrium point also changes.

You can see this in Figure 4, where Demand Curve 2 differs from Demand Curve 1, shown in Figure 1. At each price point, the total demand is less, so the demand curve shifts to the left.

Figure 4: Demand Shifts

Changes in any of the following factors can cause demand to shift:

- Consumer income.

- Consumer preference.

- Price and availability of substitute goods.

- Population.

The same type of shift can occur with supply. When supply decreases, the supply curve shifts to the left. When supply increases, the supply curve shifts to the right. These changes have a corresponding effect on the equilibrium point.

Changes in supply can result from events such as:

- Changes in production costs.

- Improved technology that makes production more efficient.

- Industry growth or shrinkage.

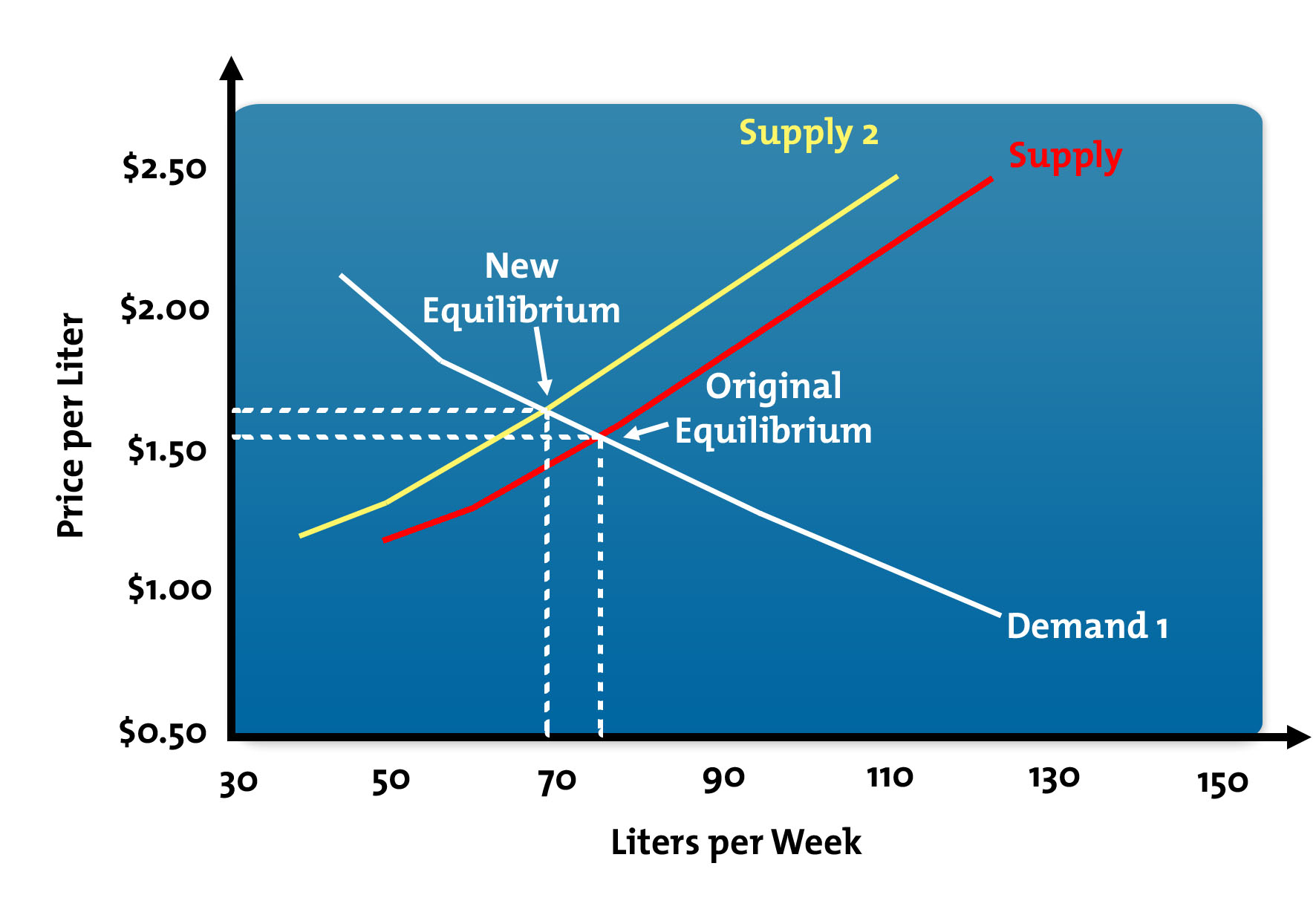

To consider our example one more time, let's say that drilling costs have increased and the oil companies have reduced the supply of gas to the market (Supply 2). The result is a higher equilibrium price, as shown in Figure 5.

Figure 5: Change in Market Equilibrium

You can use supply and demand curves like these to assess the potential impact of changes in the price that you charge for products and services, and to consider how shifts in supply and demand might affect your business.

Key Points

Although the phrase "supply and demand" is commonly used, it's not always understood in proper economic terms.

The price and quantity of goods and services in the marketplace are largely determined by consumer demand and the amount that suppliers are willing to supply.

Demand and supply can be plotted as curves. The point at which the two curves meet is known as the market quantity supplied. The market tends to naturally move toward this equilibrium – and when total demand and total supply shift, the equilibrium moves accordingly.

Understanding this relationship is key to analyzing your market, setting price points effectively, and allocating company resources in a cost-effective way.

This site teaches you the skills you need for a happy and successful career; and this is just one of many tools and resources that you'll find here at Mind Tools. Subscribe to our free newsletter, or join the Mind Tools Club and really supercharge your career!

Great summary of a demand curve. Understanding the dynamics of supply and demand is essential when determining the price of a product or service. Thanks for your comment.

Michele

Mind Tools Team

is shown on a graph, it has a peculiar shape that is distinctly known as the demand curve. This demand curve demonstrates the various prices and the demand for the product in respective to it.

Thank you for the positive feedback. Good luck with your studies.